The Lexicon of Auxiliary Function

Auxiliary function:

A helpful second or third function, according to Jung’s model of typology, that has a co-determining influence on consciousness.

Absolute sovereignty always belongs, empirically, to one function alone, and can belong only to one function, because the equally independent intervention of another function would necessarily produce a different orientation which, partially at least, would contradict the first.

But since it is a vital condition for the conscious process of adaptation always to have clear and unambiguous aims, the presence of a second function of equal power is naturally ruled out.

This other funct1on, therefore, can have only a secondary importance. . . .

Its secondary importance is due to the fact that it is not, like the primary function . . . an absolutely reliable and decisive factor, but comes into play more as an auxiliary or complementary function.[“General Description of the Types,” CW 6, par. 667.]

The auxiliary funct1on is always one whose nature differs from, but is not antagonistic to, the superior or primary function: either of the irrational functions (intuition and sensation) can be auxiliary to one of the rational funct1ons (thinking and feeling), and vice versa.

Thus thinking and intuition can readily pair, as can thinking and sensation, since the nature of intuition and sensation is not fundamentally opposed to the thinking function. Similarly, sensation can be bolstered by an auxiliary funct1on of thinking or feeling, feeling is aided by sensation or intuition, and intuition goes well with feeling or thinking.

The resulting combinations [see figure below] present the familiar picture of, for instance, practical thinking allied with sensation, speculative thinking forging ahead with intuition, artistic intuition selecting and presenting its images with the help of feeling-values, philosophical intuition system.

Carl Jung and a Psychological Function

Function:

A form of psychic activity, or manifestation of libido, that remains the same in principle under varying conditions. (See also auxiliary funct1on, differentiation, inferior funct1on, primary function and typology.)

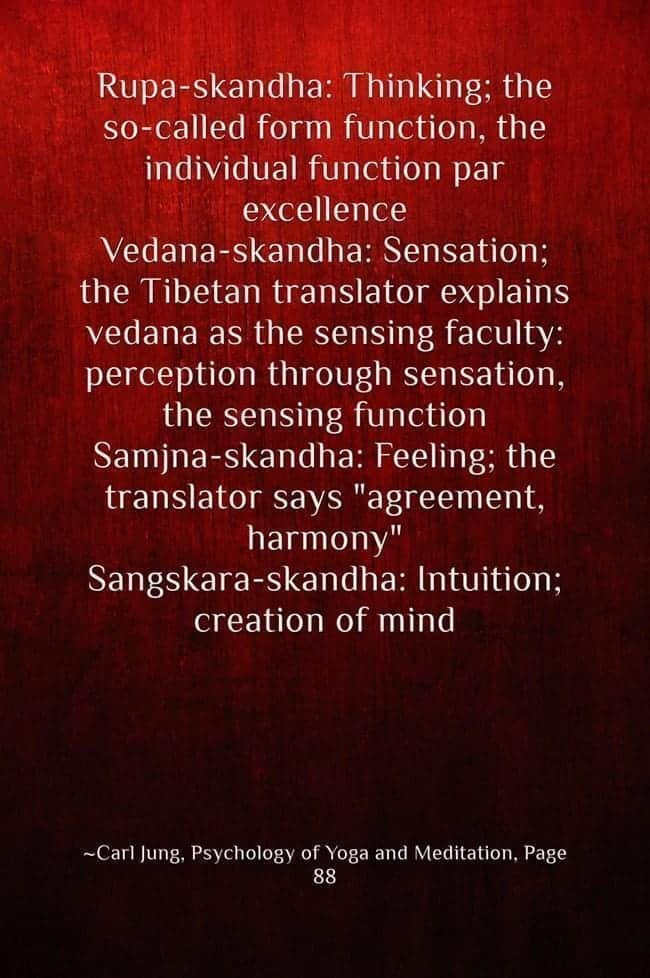

Jung’s model of typology distinguishes four psychological funct1ons: thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition.

Sensation establishes what is actually present, thinking enables us to recognize its meaning, feeling tells us its value, and intuition points to possibilities as to whence it came and whither it is going in a given situation.[“A Psychological Theory of Types,” CW 6, par. 958.]

Though all the funct1ons exist in every psyche, one funct1on is invariably more consciously developed than the others, giving rise to a one-sidedness that often leads to neurosis.

The more [a man] identifies with one funct1on, the more he invests it with libido, and the more he withdraws libido from the other funct1ons. They can tolerate being deprived of libido for even quite long periods, but in the end they will react. Being drained of libido, they gradually sink below the threshold of consciousness, lose their associative connection with it, and finally lapse into the unconscious. This is a regressive development, a reversion to the infantile and finally to the archaic level. . . . [which] brings about a dissociation of the personality.[“The Type Problem in Aesthetics,” ibid., pars. 502f.]

Carl Jung and a Psychological Function

Funct1on:

A form of psychic activity, or manifestation of libido, that remains the same in principle under varying conditions. (See also auxiliary funct1on, differentiation, inferior funct1on, primary function and typology.)

Jung’s model of typology distinguishes four psychological funct1ons: thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition.

Sensation establishes what is actually present, thinking enables us to recognize its meaning, feeling tells us its value, and intuition points to possibilities as to whence it came and whither it is going in a given situation.[“A Psychological Theory of Types,” CW 6, par. 958.]

Though all the funct1ons exist in every psyche, one function is invariably more consciously developed than the others, giving rise to a one-sidedness that often leads to neurosis.

The more [a man] identifies with one funct1on, the more he invests it with libido, and the more he withdraws libido from the other funct1ons. They can tolerate being deprived of libido for even quite long periods, but in the end they will react. Being drained of libido, they gradually sink below the threshold of consciousness, lose their associative connection with it, and finally lapse into the unconscious. This is a regressive development, a reversion to the infantile and finally to the archaic level. . . . [which] brings about a dissociation of the personality.[“The Type Problem in Aesthetics,” ibid., pars. 502f.]